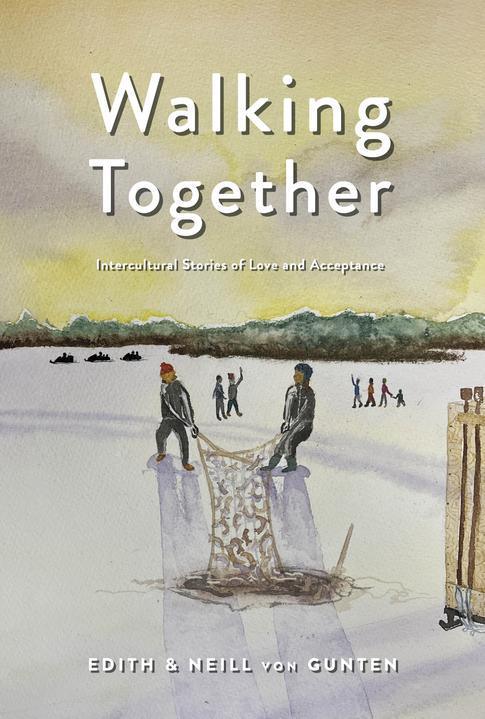

Edith and Neill von Gunten.

Since the release of their book Walking Together: Intercultural Stories of Love and Acceptance earlier this year, Edith and Neill von Gunten have been busy.

Since the release of their book Walking Together: Intercultural Stories of Love and Acceptance earlier this year, Edith and Neill von Gunten have been busy.

Over the summer they travelled north to the communities in which they lived and came to love during their time of with Native ministries for Mennonite Church Canada: Manigotagan and Hollow Water First Nation on the east shore of Lake Winnipeg, and Pine Dock, Matheson Island, Riverton, and Fisher River First Nation.

They brought copies of their book along and say the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

- Order Walking Together from CommonWord

- Attend or watch the book launch on Sept. 29 at 7 p.m. CDT at CommonWord

“I had some really good conversations with people,” said Edith von Gunten. “Hearing about the overall Mennonite history has been very humbling.”

“One comment has been ‘Mennonites are peacemakers,’” said Neill von Gunten. “You have come into our community and where there were conflicts or difficulties between groups, you helped bring us together as a people.”

Walking Together’s seven chapters are based on the Seven Teachings of the Ojibwe, something the writers asked permission to do from Elder Stan McKay of Fisher River Cree Nation, whom the von Guntens have a good relationship with; Elders Barbara and Clarence Nepinak of Winnipeg who are Ojibwe knowledge keepers and educators; as well as Metis Elder Norman Meade of Winnipeg and Manigotagan, Manitoba. The book recounts many stories from their experiences in ministry spanning 50 years, from Chicago in the 1960s to the shorelines of Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba.

In our latest interview, Neill and Edith share their thoughts on the process of writing the book, what’s crucial for ISR justice work to continue in the regional churches and how congregations can step up to the plate.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did anything surprise you in the process of writing the book?

Edith: When we asked the Elders about the Seven Teachings, none of them hesitated and Stan McKay said, ‘You know, I’m in an Elders group in Fisher River and I’ve been thinking that we should do something like that ourselves and get the people, the Elders, to tell their stories. The Seven Teachings is one way we could do that.”

Neill: We’ve been contacted by a few churches who want to do a book study, asking what does it mean for us individually and as a church, how does our story fit into those seven teachings, what can we learn from it? That’s rather exciting.

Edith: That’s why we put the study guide in the book, too. We shouldn’t have been surprised when we got several invitations this fall to participate in things.

What kinds of invitations?

Neill: Well, you name it.

Edith: We're speaking at an adult education class in our own congregation. We’re being interviewed at the Senior’s Tea (laughs).

Neill: Another church has invited us to their Sunday School to do an introduction to the study. Another congregation is going to do a seven-week study of the book. We're teaching a CMU course for 55+ in March.

Edith: But the church holding the seven sessions, we told them we would come to the first session and introduce it, but after that they need to work at it themselves.

Neill: “It's your struggle, it's your questions, and we'll get you going on that.” We just don’t have the time to do all seven, but I think it means more if it reflects their own walk of reconciliation and their own stories as a congregation and as individuals. That's important.

Is there a chapter or story or teaching in the book that is particularly meaningful for each of you?

Neill: For me, it is the chapter on humility. That touched me because humility, according to the Elders, expresses wisdom. You need to be wise, but you need to be humble and you need to reflect that in everything you do and everything you say. That's not always easy for us to do.

Edith: I wanted to make sure we shared stories of the mothers and the grandmothers in all the communities, the strong roles they play and what I learned from them. They were such a strength to all of us. To the whole family.

When you're living in these communities that are so culturally different from your own, how does that interact with your own personal lives and your relationship with each other? Did you adopt the same ideas and practices and was there tension between doing that and how you were brought up?

Neill: I think the tension for me came the most when I moved back to the city and we moved into the office at Mennonite Church Canada in Winnipeg. The first three or four months I would go down for coffee and I didn't feel at home there. I didn't have anything to say, I didn't know what to talk about, the language was so different. Because of the culture I had become part of up north, I could no longer relate to the culture in the city. That was a struggle for me. I realised that's how a lot of Indigenous people feel when they move to the city. Now when I go up north I'm just like, "We're home.” It feels so good and comforting. That was my journey, but it took awhile to grow into that.

Edith: We've often said that one of the advantages that we had is that our birth families are in Indiana, which is very, very far away. We noticed a difference in the staff who came up north and had relatives in southern Manitoba; they struggled way more than we did because we immersed ourselves. Women in the community became our children’s grandmothers and men became their grandfathers. With our family of origin so far away, they became our family.

With our family of origin so far away, they became our family.

Neill: We supervised a lot of staff up north who came from Elim Bible Institute, Swift Current Bible Institute, CMBC, CMU and other places, for a month in January or during the summer. One thing I always told them, when you were at Matheson Island or Manigotagan, for example, “This is your home. You have a biological family, that's great, but for these next weeks or months this is your home. Start building relationships, they will trust you, it will change your life.” And for those who did that, it did. For those who didn't, they never accomplished much. That was always our message, because that's what we did.

How did your concept of ministry evolve?

Neill: Chicago was the turning point. It was so different from our home background. It opened our eyes to what's happening in the world. When we went from CMBC up north to Manigotagan, we were already saying we need to pay attention to the community around us and listen to the Elders. So our style of ministry evolved. When I saw Martin Luther King, Jr. in Chicago, participated in his marches and saw his approach, it gave me a lot of ideas as to what needs to be done.

When I saw conflict in Chicago and then conflict up north between families, communities or in churches, or at camp with kids, I knew there was always another way. What is that way? We need to find it. That always was a welcome challenge, finding another way of dealing with conflict in a good, constructive way.

Edith: The church in Chicago was a predominantly Black congregation. When they read the Bible, it was with a different lens than where we grew up in Indiana. Because of the oppression they faced, they heard passages of Scripture differently. During sharing time there would be personal things, but also calls to help with specific things in the community. It was a whole different way of looking at ministry.

Neill: Tell them about Moses and the cultural adoption.

Edith: When we moved to Riverton, we often shared sermons. Once, when Neill was preaching, a woman interrupted him when he was talking about Moses and said, “That is a cross-cultural adoption.” This woman was working in social services, helping families. It was like a light bulb went on in her mind.

The same thing happened when we were talking about Jesus’ temptations. "That's like a vision quest," somebody said. So I would try to find those links to spark an idea in somebody’s mind. We learned that in Chicago as well.

Neill: It is awesome how people see Scripture with different cultural eyes than we do.

What do you think is the most important thing for the Mennonite church to do as commitment to ISR justice work evolves to be regionally focussed?

Neill: I'm excited about the possibilities. I’m concerned about keeping the work growing. Hopefully there's a leader because it's a lot of work for somebody in each province. I hope there's somebody that's going to take that flagship up and run with it and bring people onboard. Or it might take several people to do that. As long as they're committed. If it’s all volunteers, it will be easy to say, "I'm too busy, I don’t have time," and then it starts to lose focus.

Edith: But there's so many questions out there that people are asking us. The country is ramping up and it looks like we're going backwards, and so we have to keep momentum going. It's going to depend who has the new nationwide half-time position, but mostly it's going to depend on each of the regions.

Neill: And that's where the strength could lie, because it broadens it out. I know there’s commitment by individuals, and that’s great, but is it enough to carry forward for the next five, ten years? We pray so.

Does your congregational engagement feel different now? Has the book opened up something?

Edith: Requests from churches to come and speak have been much less as time’s gone on, but they’ve continued. When we retired in 2011, people in the Indigenous communities told us, "Now is your time to help your own people learn more. You've helped us and you've been with us and now your work is with your own people." We've taken that seriously. Whenever we're asked we get involved as much as we can.

Neill: I think in many ways that's what this book was intended to do, to continue the discussion, using our lives as an example. Hopefully others will see their lives and how they can move forward as individuals and congregations. I think the key for me was to be as honest as I know how: this is me, and if I'm honest, hopefully others will be honest in their own reflections and their own congregation. We made ourselves vulnerable. That's important because we all need that sense of being vulnerable to ourselves and to each other, as a congregation and a community.

What's an example of being vulnerable or honest that you experienced?

Neill: One example in the book is when Norman Meade asks me, “Did you think that you were better than us when you came to Manigotagan?” I said, “Yes, I thought I had so much to teach you, since I was just out of Bible college (at CMBC)." I was vulnerable in saying that. Loretta Meade Ross, in the afterword, said, "I think every Indigenous person would like to ask that question of every individual." I’ve thought, wow. I guess that's what I mean.

What do you offer as encouragement or suggestions to congregations who are interested in this work but haven't reached out in a formal way to Indigenous neighbours or their nearest First Nation community?

Neill: Somebody said "when the table is set, go." If there's an event happening in your community, go, take part. If it's a powwow, if it's a truth and reconciliation day, go to it. Those are small steps without being threatened or feeling intimidated. As you’re standing in the circle you'll begin to talk with people. Another way would be to invite somebody into the congregation that someone else in the congregation might have a relationship with. Just sit down and talk. Storytelling is such a good way of beginning to hear each other.

Edith: It doesn't have to be anything –

Neill: --profound.

Edith: We always think it has to be something really special. But we’ve heard of people asking permission to go into a seniors’ residence that has a number of Indigenous people in it, to just sit around and talk over tea.

Neill: One comment I heard from Elders was, "Come, waste some time with us." (Laughs)

Edith: Some people are so afraid they're going to be colonialist. They don’t go because they're afraid they're going to do something wrong. It's just so much easier to go with an open heart and listen and be respectful. You don’t have to do anything else.

It's just so much easier to go with an open heart and listen and be respectful. You don’t have to do anything else.

Anything else you’d like to share?

Neill: I guess I've always felt that, in our ministry that we're often very misunderstood.

Edith: And caught between two worlds.

Neill: You feel caught because you see both sides so clearly. I know I'm not the only one that feels that way. It has to do with misinformation out there, believing this stuff that's out there and not really hearing and knowing the truth.

Edith: When we've gone to churches and spoken, and especially in Sunday School class, we’d say that there's no question that's too dumb, hoping they would ask us if they couldn't ask an Indigenous person.

Neill: One time somebody asked a question that was very racist. My mind was racing. I stopped and didn't say anything for quite a little while. Finally, I just said, "You know, that hurts." That got everybody’s attention. I very carefully told them what hurt—because you’re not only hurting me but you're hurting the people that are my relations.

One more story: I attended a funeral of a fellow who was murdered, from a northern reserve. There were three chiefs there whom I knew (two past, one present) and it struck me while I was giving the sermon. I said, "Why does your community allow these murders to take place? Do something about it. You've got a lot of wisdom, you've got a lot of Elders, you've got strength here, why are you standing for this?" After the service all three of the men came up to me at the end and said, "You're right, why are we standing for it as a community?"

Edith: They actually came up together.

Neill: We all talked about it for quite awhile. It helped those three men, who were so close to each other, to begin talking. How do you begin that process, even in our churches, to get people talking to each other?

Edith: I thought you were going to use the example of a Sunday School class –

Neill: Oh, that one. [Laughs]

Edith: –where we asked, “Does anybody here have any Indigenous friends, or people that you relate to?" Not one person said a thing. Then finally one person said, "Well, I do. I work in the thrift shop and I get to know some of the women that come in." And she said –

Neill: —with tears—

Edith: "When we see each other on the street or in the store, then we talk." Pretty soon other people started sharing. The pastor was floored because nobody had ever shared that. It was because one person was brave enough to share.

Edith: Anyway, hopefully we opened some doors for people to continue to share as well.

We have one month left to reach our Global Companionship goals for this year.

We are inviting your support for an additional $48,000 by the end of March!

Why Global Companionship?

The goal of mission is not primarily aid (humanitarian assistance); it’s not even partnership. We engage in mission to establish friendships that lead to the formation of a new people in the world... If we are in Christ, we have become part of a new creation.