January 28th, 2026Overturning the tables of injustice in Palestine

In November 2025, I was in the West Bank, Palestine, attending the Kairos conference as a visitor seeking to learn and to listen in solidarity to Palestinians living amid decades of extreme violence. During my time there, I encountered profound sorrow rooted in realities that Palestinians themselves describe as long-standing occupation and military control under Israeli authority. Witnessing these realities challenged me deeply, as they stand in tension with the way of Jesus and with the peace we, as Anabaptists, claim to follow.

I arrived near the end of the olive harvest season and heard many stories about the dangers Palestinians face simply trying to harvest their olive trees. Palestinians are often physically attacked by Israeli settlers who have built communities throughout the West Bank, settlements considered illegal under international law. One of my Israeli friends from Jerusalem told me that it is illegal to cut down an olive tree inside Israel. Yet in the West Bank, this happens frequently, as settlers destroy Palestinian-owned olive trees, devastating Palestinian livelihoods and local economic stability.

Palestinian-owned Olive Trees are often destroyed by Israeli settlers

I also experienced how difficult it is to move throughout the West Bank, a landscape shaped by concrete separation walls and checkpoints, roadblocks, and gates that the Israeli military can close at any time. As a result, people can be delayed for hours simply trying to travel short distances. One roadblock that shocked me was a car filled with thousands of bullet holes, left in place to obstruct movement. Yet, the most painful part of my time was listening to Palestinians share their own stories.

From Bethlehem, a concrete wall blocks the view toward Jerusalem. A painting on the wall imagines the skyline beyond.

I shared lunch with Palestinians from Jenin whose homes had been raided and destroyed by the Israeli military, forcing them to flee. Jenin, classified as Area A and intended to be governed by Palestinians, has seen significant displacement due to ongoing military activity and control. Now, as I write this, I am aware of reports that the last 15 families in the village of Ras Ein al-Auja are being forced to flee amid intensified Israeli settler violence and harassment. Listening to these experiences, I find myself asking what it would mean if this were happening to our homes in Canada. What if we lived under curfews, home demolitions and heightened surveillance, passing through militarized checkpoints and guns pointed at us each time we left our communities?

Sharing lunch with Palestinians, eating Palestinian cuisine

I also met several teenagers who had been shot by the Israeli military, but one boy’s story in particular stayed with me. He was fourteen years old when it happened. He was shot in the neck, and the bullet exited through his cheekbone, permanently damaging his vision and face. He survived and now lives with the lasting consequences of that injury. He was simply walking with friends when it happened. Listening to his story, I was confronted with the impact of violence on children growing up under occupation.

An anthem of hope: may peace prevail on earth, in Palestine, Israel and beyond

I visited a Palestinian farm surrounded by five Israeli settlements. Because of settler expansion, the family cannot build freely or access electricity or running water. Instead, they have developed resilient and creative ways to survive, using solar panels, collecting rainwater, and adapting caves as shelter.

What stayed with me most about this family was their response. Despite ongoing challenges, they refused to let hatred define them. They described maintaining a peaceful and resilient way of life, grounded in the conviction that evil cannot be overcome with evil, a principle deeply familiar within the Mennonite tradition.

A cave used as a worship space

Finally, I met several priests and pastors, including a bishop, who asked a question that has stayed with me since: “What does reformation look like after two years of genocide in Gaza?”

This was the first time I had heard someone in the church, someone in a position of power, name what is happening without hesitation.

This bishop’s clear stance on what is happening echoes a core conviction articulated in the Kairos Palestine 2 document, written by Christian Palestinians: faith cannot be neutral in the face of injustice. The Kairos document insists that faith requires truth-telling and courageous action, and it calls on churches in the West to name reality as Palestinians themselves experience it. In Gaza, the document describes a population facing genocide, with thousands displaced, wounded, or buried beneath the rubble, and with water, medicine, and shelter scarce or nonexistent. Children there have known little beyond war, fear, and hunger. In the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the document describes a different but connected reality, one described by Palestinians as shaped by settler colonialism and apartheid enforced through checkpoints, military raids, home demolitions, land confiscation, and daily humiliation.

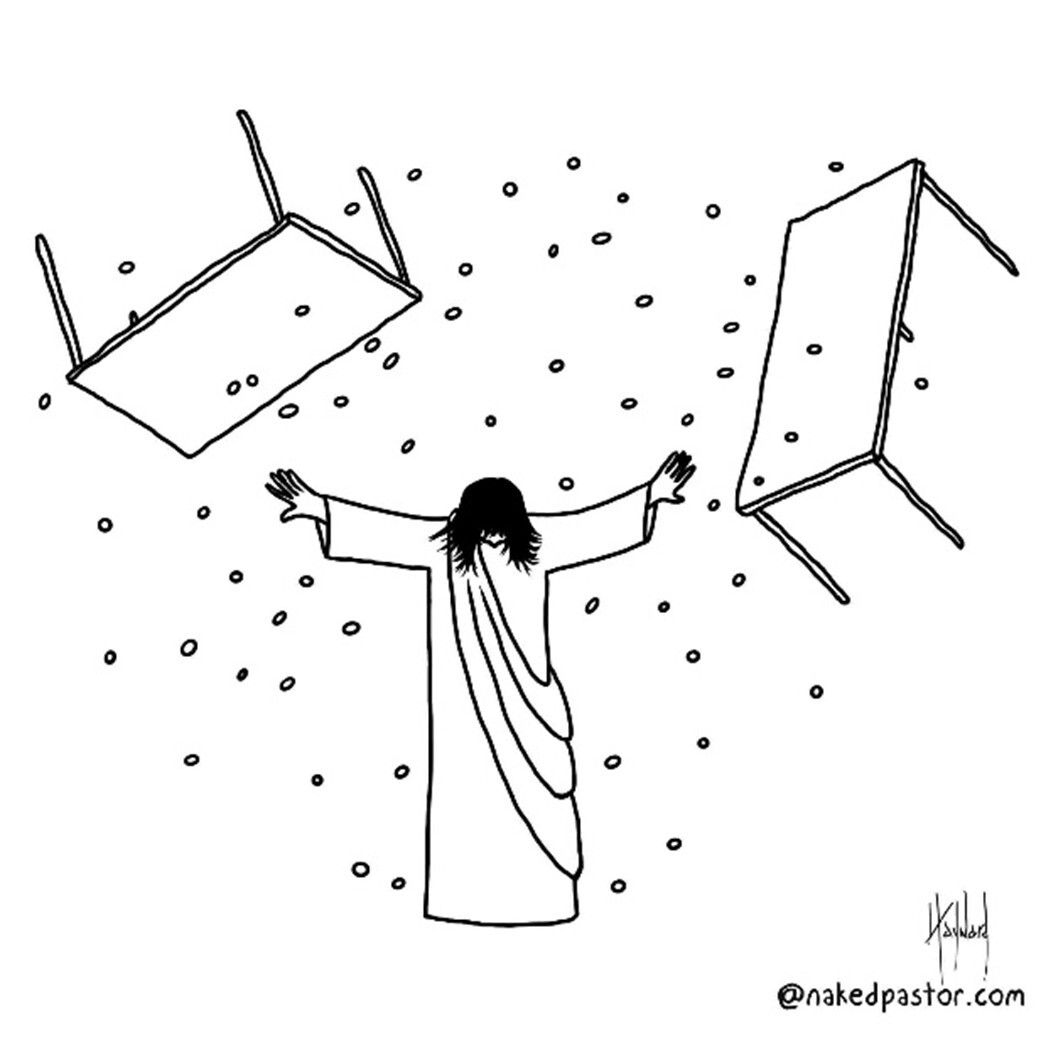

Considering these stories, I found myself asking: What would Jesus do if he witnessed teenagers being shot in the context of ongoing military operations? What would Jesus do if he knew medical aid were blocked from reaching bombed churches, schools and hospitals? Would he remain silent or would he confront systems of violence and overturn the tables of injustice?

Here in Canada, many of us live with immense privilege and freedom, and such freedom carries responsibility that requires action.

This year, may we reject theologies that justify oppression; may we speak truthfully, amplifying Palestinian voices that have been silent for far too long; and may we overturn the tables of injustice, urging our governments to uphold international law and the dignity of every human.

Like Jesus, we can overturn the tables of injustice